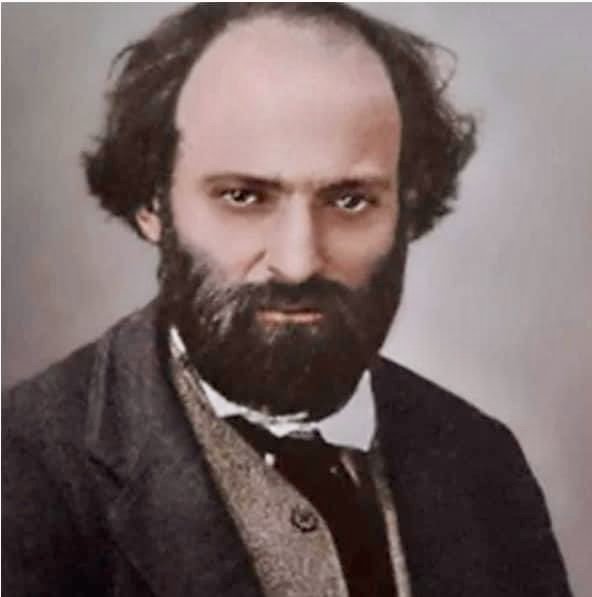

Paul Cezanne

PLEASE NOTE - SEE SAMPLES OF ARTWORK AFTER BIOGRAPHY SECTION

Paul Cézanne (19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French artist and Post-Impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th-century conception of artistic endeavor to a new and radically different world of art in the 20th century. Cézanne is said to have formed the bridge between late 19th-century Impressionism and the early 20th century's new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism.

While his early works are still influenced by Romanticism, he arrived at a new pictorial language through intensive examination of Impressionist forms of expression. He gave up the use of perspective and broke with the established rules of academic art and strived for a renewal of traditional design methods on the basis of the impressionistic color space and color modulation principles. Cézanne's often repetitive, exploratory brushstrokes are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. He used planes of colour and small brushstrokes that build up to form complex fields. The paintings convey Cézanne's intense study of his subjects. Both Matisse and Picasso are said to have remarked that Cézanne "is the father of us all".

His painting provoked incomprehension and ridicule in contemporary art criticism. Until the late 1890s it was mainly fellow artists such as Pissarro and the art dealer and gallery owner Ambroise Vollard who discovered Cézanne's work and were among the first to buy his paintings. In 1895 Vollard opened the first solo exhibition in his Paris gallery, which led to a broader examination of the artist's work.

Paul Cézanne was the first artist to begin breaking down objects into simple geometric shapes. In his much-quoted letter of 15 April 1904 to the painter and art theorist Émile Bernard, who had met Cézanne in his last years, he wrote: "Treat nature according to cylinder, sphere, and cone and put the whole in perspective, like this that each side of an object, of a surface, leads to a central point.” Cézanne realized his painting ideas in the paintings of Montagne Sainte-Victoire and the his still-life’s. In his pictorial conception, even a mountain is understood as a superimposition of forms, spaces and structures that rise above the ground.

Émile Bernard wrote of Cézanne's unusual way of working: "He began with the shadow parts and with one spot, on which he put a second, larger one, then a third, until all these shades, covering each other, modeled the object with their coloring. It was then that I realized that a law of harmony was guiding his work and that these modulations had a direction preordained in his mind.” In this preordained direction, for Cézanne, lay the real secret of painting in the context of harmony and the illusion of depth. To the collector Karl Osthaus Cézanne emphasized on 13 April 1906 during his visit to Aix that the main thing in a picture is the meeting of the distance. The color must express every leap into the depths.

The French philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard argues in his work Misère de la philosophie, that Cézanne has, so to speak, the sixth sense: he senses the reality in the making before it is completed in normal perception. So the painter touches on the sublime when he sees the overwhelming quality of the mountainous landscape, which can neither be represented with normal language nor with the usual painting technique. Lyotard sums it up: "One can also say that the uncanniness of the oil paintings and watercolors dedicated to mountains and fruits derives both from a deep sense of the disappearance of appearances and from the demise of the visible world."

Cézanne's stylistic approaches and beliefs regarding how to paint were analyzed and written about by the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty who is primarily known for his association with phenomenology and existentialism. In his 1945 essay entitled "Cézanne's Doubt", Merleau-Ponty discusses how Cézanne gave up classic artistic elements such as pictorial arrangements, single view perspectives, and outlines that enclosed color in an attempt to get a "lived perspective" by capturing all the complexities that an eye observes. He wanted to see and sense the objects he was painting, rather than think about them. Ultimately, he wanted to get to the point where "sight" was also "touch". He would take hours sometimes to put down a single stroke because each stroke needed to contain "the air, the light, the object, the composition, the character, the outline, and the style". A still life might have taken Cézanne one hundred working sessions while a portrait took him around one hundred and fifty sessions. Cézanne believed that while he was painting, he was capturing a moment in time, that once passed, could not come back. The atmosphere surrounding what he was painting was a part of the sensational reality he was painting. Cézanne claimed: Art is a personal apperception, which I embody in sensations and which I ask the understanding to organize into a painting.